Bayesian Reaction Optimization Using EDBO - Part IV

Published:

Part IV - Bayesian Reaction Optimization Workshop

In part I we installed the pre-release of EDBO and ran basic functionality tests. In part II we got a handle on some simple use cases for the software. In part III we got an idea of how to quickly use EDBO to define, encode, and carry out Bayesian reaction optimization. In this post, we will develop a custom EDBO pipeline for you to apply in your own research. The idea here is for us to develop a notebook which can be used to carry out routine reaction optimizations.

Define your problem

To start, we need to identify a problem of interest - perhaps a reaction optimization you are currently working on or a problem investigated in the past. Ideally, you can drum up an interesting system in which you have some preliminary data. Next, before writing any code we should figure out what the best objective, reaction space, and experimental setup is for the application. Recall the problem definition section introduction in part III.

Encode the reaction space

Once we have defined the problem we are ready to open up a Jupyter or Jupyter Lab notebook and get to work. In anaconda prompt (or Mac/Linux terminal).

conda activate edbo

jupyter lab

Next, we can assemble the lists of catalysts, reagents, concentrations, temperatures, etc. which will define the search space. Keep in mind that the larger your search space the more computational resources you will require (for this demo I would try to limit the size to < 1,000,000 points). You could assemble the lists as a CSV file or directly in the notebook. Note that if you don’t have SMILES strings or proper chemical names for reagents of interest you can use ChemDraw to get these.

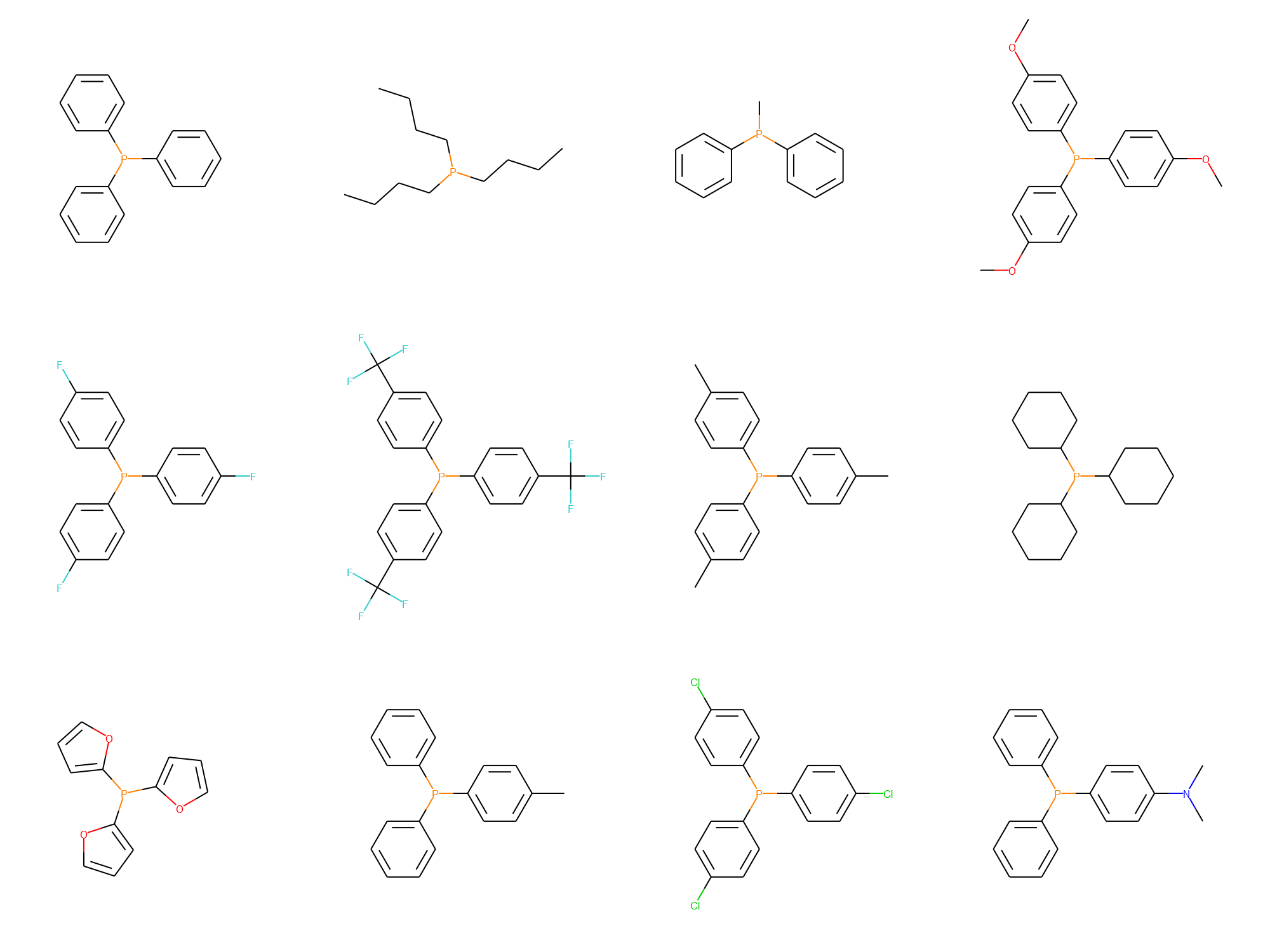

Example reaction parameter specifications:

import numpy as np

# As a list

ligands = ['C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1',

'CCCCP(CCCC)CCCC',

'CP(C1=CC=CC=C1)C2=CC=CC=C2',

'COC1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=C(OC)C=C2)C3=CC=C(OC)C=C3)C=C1',

'FC1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=C(F)C=C2)C3=CC=C(F)C=C3)C=C1',

'FC(F)(F)C1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=C(C(F)(F)F)C=C2)C3=CC=C(C(F)(F)F)C=C3)C=C1',

'CC1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=C(C=C2)C)C3=CC=C(C=C3)C)C=C1',

'C1(P(C2CCCCC2)C3CCCCC3)CCCCC1',

'C1(P(C2=CC=CO2)C3=CC=CO3)=CC=CO1',

'CC1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)C=C1',

'ClC1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=C(Cl)C=C2)C3=CC=C(Cl)C=C3)C=C1',

'CN(C1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)C=C1)C']

# You can encode any controlled reaction paramter

lights = ['kessel lamp', 'BLED strip']

# Evenly spaced continuous variables using numpy

temperatures = np.linspace(0, 100, 11)

These component lists will then define the component and encoding dictionaries. In python dictionaries are defined as {'key':value } pairs. Note that the keys must match between the components and encodings.

components = {'ligand':ligands,

'temperature':temperatures,

'light':lights}

encodings = {'ligand':'mordred',

'temperature':'numeric',

'light':'ohe'}

Setting up the optimizer

The next step is to set up our optimizer. Here we will use a minimal configuration but feel free to experiment with options available in the documentation. Let’s say we can only run 8 experiments at a time.

from edbo.bro import BO_express

bo = BO_express(components,

encodings,

batch_size=8,

target='yield')

Once the optimizer finishes building the search space we can make sure the candidate reactions look appropriate. First let’s check out the index of experiments without encoding:

bo.reaction.base_data[bo.reaction.index_headers].head()

| ligand_SMILES_index | temperature_index | light_index | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | 0 | kessel lamp |

| 1 | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | 0 | BLED strip |

| 2 | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | 10 | kessel lamp |

| 3 | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | 10 | BLED strip |

| 4 | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | 20 | kessel lamp |

And with encoding:

bo.obj.domain.head()

| ligand_ABC | ligand_SpMax_A | ligand_SpMAD_A | … | temperature | light=kessel lamp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.390816 | 0.841258 | 1 | … | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0.390816 | 0.841258 | 1 | … | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0.390816 | 0.841258 | 1 | … | 0.1 | 1 |

| 3 | 0.390816 | 0.841258 | 1 | … | 0.1 | 0 |

| 4 | 0.390816 | 0.841258 | 1 | … | 0.2 | 1 |

And then check the chemical structures for validity, either experiment by experiment using the bo.reaction.visualize method or all at the same time using the ChemDraw class.

from edbo.chem_utils import ChemDraw

cdx = ChemDraw(bo.reaction.base_data['ligand_SMILES_index'].drop_duplicates().values,

row_size=4)

cdx.show()

Loading data

If we didn’t have any data available or wanted to ensure an unbiased start to the optimization then we would next carry on as in the previous posts by using the init_sample method to choose initial experiments to run. However, in today’s exercise we have preliminary data which we would like to read into the optimizer. EDBO doesn’t have a built in method for loading data unless it has the same indices as the BO objects domain (as you get when you call bo.export_proposed() for example). However, there are a number of ways to get this done. For example, we could find the experiments that correspond to the preliminary data by hand (or in python) and load the CSV using bo.add_results('results.csv'). As an illustration, let’s write a quick function to do this for us. We will need to open up excel and tabulate our data in the same way it is listed in the index (as above) and save it as a CSV file. For this example the first entries in the CSV file might look like the following:

| ligand_SMILES_index | temperature_index | light_index | yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | 0 | kessel lamp | yield0 |

| C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | 0 | BLED strip | yield1 |

Note that in this example, all of the entries in the table must correspond to experiments actually in the reaction space. Of course this is not a requirement but since it is a more advanced usage case we won’t cover it in this tutorial. Next, we define and run a function for loading the data.

import pandas as pd

# Define a function to load experiments

def add_unindexed_experiments(results_path):

"""

EDBO is currently designed to be used from end to end. This function will

load experimental data which is not indexed by the optimizers search space

so that we can use the data that has already been collected without having

to look up the indices.

"""

from edbo.objective import objective

# Import points and load the reaction space

results = pd.read_csv(results_path)

domain_points = results.iloc[:,:-1]

index = bo.reaction.base_data[bo.reaction.index_headers].copy()

# Get corresponding points. Iterate to maintain order.

union_index = []

for i in range(len(domain_points)):

ui = pd.merge(index.reset_index(),

domain_points.iloc[[i]],

how='inner')['index'][0]

union_index.append(ui)

index_out = index.iloc[union_index]

# Make sure points are aligned

assert False not in (index_out.values == domain_points.values).flatten()

# Get encoded results

encoded_results = bo.obj.domain.iloc[union_index].copy()

encoded_results[results.columns.values[-1]] = results.iloc[:,-1].values

# Update the objective

bo.obj = objective(domain=bo.obj.domain,

results=encoded_results)

return encoded_results

# Run the function

add_unindexed_experiments('results.csv')

Running the optimizer

We already covered this topic in the previous posts. Thus, we are going to leave this section open ended. At the very least, everyone should run the optimizer (bo.run()), check out the model’s fit to the data (bo.model.regression(), investigate the acquisition summary (bo.acquisition_summary()), and check out the proposed experiments.

Wrapping up

This wraps up the preliminary tutorial on using EDBO to carry out Bayesian reaction optimization. If there is interest, I would be happy to talk more about advanced usage, tuning the optimizer, or tackling specific problems in future posts. In the mean time, if you are interested in using EDBO to tackle computational optimization problems check out my recent post on Automatic Design of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibitors via Machine Learning & Molecular Docking.